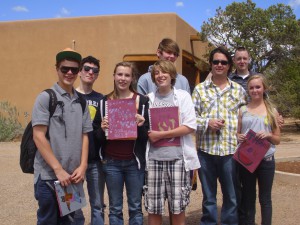

Santa Fe has some very cramped parking lots, one of which I navigate every Thursday with a minivan full of teenagers. We grab coffee and chai at Downtown Subscription—the best place in town to handle a gaggle like us—as a treat after visiting Wood Gormley Elementary, where the eight of us teach writing to fourth-graders.

Santa Fe has some very cramped parking lots, one of which I navigate every Thursday with a minivan full of teenagers. We grab coffee and chai at Downtown Subscription—the best place in town to handle a gaggle like us—as a treat after visiting Wood Gormley Elementary, where the eight of us teach writing to fourth-graders.

After our first visit this year, we sauntered back toward the minivan and found our path blocked by a midsize car sandwiched between two pickups. The elderly driver revved in reverse, and we could all see the crack she created in the other vehicle’s bumper elongate like the mouth in Edvard Munch’s painting “The Scream.” Teenagers are not subtle creatures, so they started to point and utter PG-13 profanities loud enough for the entire parking lot to hear.

“Get in the van,” I commanded and led them around the train wreck. Once we were on the other side, the car in question moved forward and smashed the bumper of the vehicle in front.

“That was awesome!” one of my charges yelled.

“She’ll never get outta there,” another added.

I hurried them. “Get in the van. No heckling until you are safely inside the cabin doors.”

Even though the Homer Simpson-style driving lesson had happened to someone else and occurred only moments before, the teens immediately started telling the war stories I’d hear in the hallways for weeks.

“You see that? I was this close to the smashup. Almost crushed my legs.”

“That was crazy, dude. Why didn’t they get outta the car? I shoulda drove.”

My teaching assistant, Callie, was riding shotgun and, as any good assistant would, she followed my lead by rubbernecking in the side view mirror. “I think they’re going to leave, Rob,” she said with the concern of someone who had actually paid attention in ethics class.

Checking the rearview, I saw what Callie saw: The nose of the car was almost free and aimed toward the exit. I closed my eyes and sighed. After a full day of teaching 17-year-olds to understand a book about a solitary man living near a Massachusetts pond, and then corralling other teens to help instruct 26 fourth-graders, I now had to admonish two octogenarians for a possible hit-and-run. Way too much math for one day, and I hadn’t even gotten to the abandoned racetrack where I would later help hold soccer practice for a dozen 9-year-olds.

“All right, all right,” I said to my moral compass. “Wanna come?”

“No way.” Callie smiled like a true whistleblower.

Walking over, I saw a woman with white hair pulling at the steering wheel while a man seated next to her rubbed his knees nervously. They both obviously regretted entering a parking lot with spots designed for Power Wheels cars with 12-volt batteries.

“Um, hi,” I started, feeling like an awkward teenager telling his teacher that his shirt was on inside out. “I can’t let you go unless you leave notes for those two vehicles.”

The driver was still wrestling with the wheel while the man, obviously agitated, barked at me: “What do you mean?”

“I have a car full of students, and we just witnessed you bash into both these cars.”

“We didn’t hit that one.” He nodded toward the truck in front of him.

I stepped to the end of his midsize where the headlamp hung like a disgorged eyeball. The other car’s bumper had more dents in it than Gary Busey’s skull. “Um, the evidence tells a very different story.”

“He’s right, he’s right,” the driver relented. “Let me just get out here.”

“What?” I said, whipping out my cell, ready to go code blue and call 911 on Bonnie and Clyde.

“I mean into a better parking place.”

“Fair enough,” I said and tucked my cell back in my pocket. My work there was done.